|

| The morning after - charred remains of the fire's path. The Hotel Conneaut stands untouched in the background. |

As the morning darkness of December 2, 1908, dissolved into daylight, a scene of utter destruction revealed itself along the shores of Conneaut Lake. Wisps of smoke twisted feebly from the charred debris of Exposition Park. The sight of such amusement for so many just months earlier now offered only sooty outlines and blackened, smoldering heaps made all the more pronounced by thin, ragged patches of snow.

Exhausted firemen and volunteers shuffled along gathering their buckets and hoses in preparation for the return to their stations. They had just battled what, for some, would be the biggest blaze they would ever witness, and certainly the most destructive in the park’s history. Had the fire occurred during the height of the summer season, the disaster would likely have been catastrophic. Instead, despite the loss of over forty structures, thankfully no one perished.

A Quiet Evening

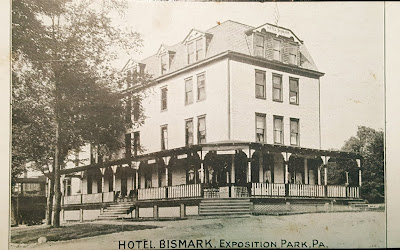

Like the majority of summer resorts, Exposition Park was mostly deserted save for the Lawrence and Reed families as well as C. W. Meyer, the operator of the Miniature Railroad, and Allison Fouce who oversaw the park during the winter months. At the Hotel Bismark 20 people were staying as fulltime boarders which included a small custodial staff and employees of the Meadville and Conneaut Lake Traction Company, there to run the trolley lines.The evening of December 1st faded into quiet convention as the residents and hotel guests settled into their nightly routine of reading, playing cards, or turning in early. That Wednesday had been a balmy 63 degrees, but a late afternoon front had moved through rapidly dropping the temperature into the 20’s, and a rambunctious wind now chased the spitting snow outside the hotel’s darkened windows.

The Hotel Bismark was owned by Julius Fohrman of Erie some forty miles to the north. Upon its construction in 1906, the ample structure’s design bore the Victorian features common to turn-of-the-century architecture. The Bismark appeared right at home in the park offering, like most of the resort’s hotels, a splendid wrap-around porch with gingerbread details highlighted in a dark colored trim. The flat rooftop was angled on the sides allowing gabled windows to protrude from the fourth story rooms. Displayed efficiently above the largest of these gables was the building’s moniker, “Hotel Bismark,” painted in two-foot-tall letters.

|

| The Hotel Bismark as it looked in 1908 |

By the late evening hour, the Bismark’s tenants were already snug in bed. At midnight a group of young people returning from roller skating passed by and recalled later that all was quiet. This would not last. Shortly after 1 AM, the hotel’s residents were roused from their sleep by a fateful announcement—the hotel was on fire. The cause for the mishap was unknown, perhaps a frayed electrical wire or an errant ember from a warming fire. Lingering rumors claimed it may have even been "incendiary in nature," a charge that would attract further attention in the ensuing months. Whatever the origin, the conflagration would prove disastrous.

Fires have rarely been benign, especially for amusement parks, and this one was no different. The harsh northwest winds scattered the flames and carried menacing cinders high into the air. Within an hour the enormous Dance Pavilion, the Old Mill ride, the Log Cabin, and all buildings in between had already been consumed by the inferno. By 2 AM the bowling alley on the southwest corner of Park Avenue and Center Street was lost along with Reed’s Palace of Amusements off to the south.

Mobilizing Fire Crews

A bucket brigade of local citizens assembled under the direction of Henry Ringwold, an African American man installed a few years earlier as the town's fire chief by park owner and Ringwold’s former employer, Major A.C. Huidekoper. The volunteers put up a valiant effort drenching adjacent buildings in order to stem the fire’s advance, yet despite saving the McCafferty cottage it was not enough. As one of the witnesses remarked, “The wind blew so strongly the fire appeared to walk right through the buildings.”

The alarm soon reached Meadville where Howard Dowdell, who had been appointed fire chief a little over a year before, mustered a sizable force. The firemen retrieved their teams of horses stabled at City Hall and rapidly fitted them with the quick-hitch harnesses in preparation for pulling the steam engine, J.D. Gill, as well as a ladder truck, and one of the hose carriages. A number of fireman along with city residents concerned about damages to property they owned at the park, boarded a trolley car hastily put into service at 2:45 AM. A special flat car was then attached to carry the Gill in the hopes it would arrive quicker.

Eighteen miles away from the park, in Greenville, the city’s fire brigade hurriedly ran the same drill in their attempt to reach the fire as fast as possible. Shortly after 3 AM, Chief Matt Keck along with eight firemen and three volunteers hauled an engine and 700 feet of hose to the railroad station where they planned to commandeer a special train of the Bessemer Railroad driven by Trainmaster Cutter. The plan fell apart, however, as the men struggled to load the train. Forty precious minutes were lost in what the Record Argus newspaper deemed an “unromantic” effort. Chief Keck would later lament that a simple apparatus costing $25 could have made all the difference.

Charging off into the night, Meadville crew following the same route as the trolley. The supports propped under the Mead Avenue Bridge so it could bear the weight of the larger interurban cars had recently been removed for winter, and the hooves and wheels hammered and rattled as they crossed over French Creek on their way through Fredricksburg, then west along the Harmonsburg Road. Their flight was made all the more treacherous by the weak light of the headlamps which barely extended beyond the front of their carriages.

As the Meadville contingent of firefighters and citizens rounded Conneaut Lake, a soft orange glow loomed ever larger on the horizon, and the faint smell of acrid smoke grew stronger in their nostrils. Flames reflected with brazen mockery across the lake’s surface where normally the park’s electric lights shimmered on the rippling water from May to September.

A Hellish Scene

Upon their arrival, the fire crew was met by a hellish scene. The entire Midway along Park Avenue had already been engulfed while indiscriminating sparks had ignited the Boat Pavilion near the lake’s edge. Between Center Street and Comstock flames also lapped at whatever stood in its path. Soon it became apparent that the fifth story cupolas and sweeping veranda of the Hotel Virginia would fall prey in short order if something wasn’t done.Despite their labors, the crews from Meadville and bucket brigade had little success in bringing the blazes under control as their steamers pumped innumerable gallons of water into the holocaust. The heat’s searing intensity pushed the men farther and farther back until it was clear the only hope lay in protecting the park’s remaining structures.

|

| The Hotel Virginia |

Finally, with the situation beyond desperate, a decision was made to dynamite the row of cottages and buildings on Brown Avenue that formed the last line between the menacing fire and the Virginia. It was their lone alternative if they wanted to save the second largest hotel on the grounds. Fifteen minutes later the charges were set, and the adjacent structures were blown. The Reeds who were living at the park watched as their cottage was reduced to splinters with a deafening explosion that left their ears ringing. Extreme as this was, the measure ultimately proved successful, sparing the Virginia from its demise.

The Fire's Devistation

By dawn the fire had been tamed, eventually burning itself out but not before laying waste to over half the park. Along with the Bismark, the park lost the Colonial and Puritan Hotels, and the four-story Park House as well as two other hotels owned by John Miller and Sons. Gone too were six restaurants, four novelty stands, three cottages, two shooting galleries, the poolroom, the Tea Garden, and the Penny Arcade. Among the rides, the fire had completely destroyed the Old Mill while damaging the Ferris Wheel, the Miniature Railroad, and the Three-Way Figure 8 Toboggan which lost its cars and passenger loading platform. The park’s grocery store, drug store, and bakery were also in ashes as was photographer W.W. Wilt’s studio. Collectively the value of the loss totaled $34.7 million by current standards.The Park Amusement Company suffered a major financial setback too as the fire claimed the Dancing Pavilion which also housed the park’s rental boats for winter. The Bowling Alley was lost as was the Boat Pavilion, Larry Palmer’s Cozy Corner souvenir shop, the moving picture theatre, and several smaller structures which together amounted to $37,500 in property damage, a sum equal to $6.2 million in today’s currency. According to the following day’s edition of the Indiana Gazette, the company’s losses were reported to be only partially insured.

|

| The fire's destruction outlined in red |

A Plan to Rebuild

More importantly, the fire failed to damper the park’s collective spirit. The following morning the stockholders assembled among the ruins and made a unanimous decision. As Billboard reported in its December 19 account of the fire, “Work on rebuilding will begin at once.” And it did. The Warren Mirror noted that a hundred or more men from Greenville had already been employed in the cleanup and that architects were in the process of designing new "buildings on more substantial lines and of greater beauty."The following week the shareholders, led by Henry Holcomb, met again in Pittsburgh. Cement they decided would be the material of choice, not only because it didn’t burn, but because it was also cheaper. The lake offered a seemingly limitless amount of sand and gravel, and the only remaining requirement was a cement plant which they eventually built on the park grounds.

|

| Henry Holcomb |

On January 1st, a charismatic Holcomb, formally revealed plans for a bigger, more ambitious Exposition Park, galvanizing the park’s various businessmen. In addition to the use of cement blocks, streets would widen and buildings re-plotted, most notably at Park Avenue and Center Street where the park’s crown jewel, a massive dance pavilion, would require Aldine Cottage be moved to an adjacent intersection.

Concessions owners such as John Miller and R.C. Jackson quickly committed to reinvesting in the popular Miller’s Café and longstanding Log Cabin respectively. Repairs would likewise be made to C.W. Moyer’s Northwestern Line of the miniature railroad and T. M. Horton’s Figure 8 roller coaster, while new rides and attractions would also be added.

The Fire's Origins

With preparations set in motion for reconstruction questions still remained, however, concerning the destructive fire’s origin. A reward leading to the arrest of anyone responsible was immediately issued, but the move aroused the suspicions of the insurance companies who refused to issue settlements until a thorough investigation could be conducted.In February the Middle Division of the Fire Underwriters Association sent a detective to find answers. What he discovered confirmed the suspicions. The Bismark Hotel was flailing financially, and not only did it have coverage by a Meadville agency, but it also had a number of smaller policies scattered around the country that together totaled more than the property’s value. However, if the detective expected to root out a culprit he was mistaken even after offering immunity to any guilty party. Local police and investigators soon involved themselves only to be thwarted by the same lack of evidence. No arrests were ever made.

Park's Reopening

|

| The new cement-block midway along Park Ave. in 1909. The structure would remain until the early 1990's |

As the Bessemer Railroad’s 1909 annual booklet heralded, “Out of the ashes of the old has risen the new—a New Exposition Park has been created on the shores of Conneaut Lake…” Indeed it had, and would main so over a century to come.

Sources

Castello, Michael E. Images of America: Conneaut Lake Park. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2005.

Luty, Bronson B. The Lake as is Was: An Informal History and Memoir of Conneaut Lake. Meadville: Crawford County Historical Society, 1994.

Stewart, Anne W., Moore, William B. Images of America: Meadville. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2001

Siebert, C.L., Northwestern Pennsylvania Railway. 1976

“Destructive Fire,” Alexandria Gazette, December 2, 1908.

“Exposition Park at Conneaut Lake Near Meadville Damaged by Fire,” Harrisburg Telegraph, December 2, 1908.

“Fire at Summer Resort,” Beminiji Pioneer, December 2, 1908.

“Resort in Ruins: Exposition Park at Meadville a Prey to Flames—Stopped by Dynamite,” The Marion Daily Mirror, December 2, 1908.

“Exposition Park in Ruins,” Record Argus, December 2, 1908.

“Conneaut Fire Losses: Forty Buildings Destroyed at Amusement Grounds,” The Oil City Derrick, December 3, 1908. (Courtesy Dave Brown)

“Meadville, PA Suffered Heavy Loss by Fire,” The Pensacola Journal, December 3, 1908.

“Forty Buildings at Exposition Park Go Up in Smoke,” Indiana Gazette, December 3, 1908.

"Conneaut Park to be Reconstructed," Warren Mirror, December 7, 1908.

“Big Losses by Fire,” Indiana Democrat, December 9, 1908.

“Loss by Fire at Resort,” Valentine Democrat, December 10, 1908.

“Exposition Park: Fireproof Buildings May be Erected to Replace the Burned District,” Record Argus December 12, 1908.

“Disastrous Fire at Exposition Park, Conneaut Lake PA,” Billboard, Vol. 20, December 19, 1908.

“Detectives to Probe Fire,” Record Argus, March 11, 1909.

“Nearing Completion,” Record Argus, May, 17, 1909.

Record of Climatological Observations, U.S. Department of Commerce, December 1908.

About the Author

Ron Mattocks was born and raised in Guys Mills, Pennsylvania. Following high school he joined the Army to see the world (which he did) before a career as a construction executive in Texas. Eventually Ron switched to Internet marketing, working with companies such as GMC, ConAgra, Mattel, and others. During this time he also began writing regularly for the Huffington Post, Disney's Babble, and the TODAY Show. On a summer visit to Conneaut Lake Park, Ron became suddenly fascinated with the park's origins, a fascination that lead to a passion for the county's extensive history. Today, Ron is the co-owener of Historia Inspired, LLC, and President of Client Strategy at Bull Moose Marketing in Meadville, PA. He graduated from St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas with a degree in English Literature, and is board VP of the Crawford County and board member of Northwestern PA Railroad and Tooling Museum.

* * *

Membership Plans for Everyone!

|

| Join Today! |